Class Review Notes: The Sun’s path across the sky at any place is the product of Earth’s tilt and that place’s latitude. Because the tilt remains the same throughout the year, the position of the Sun on anyone’s “celestial dome” changes. I used “apparent” above because the Sun’s path across the “apparent dome” that covers every location differs by latitude.

For example, I live at 40 degrees, one minute, 12 seconds north latitude. So, for my geographic position, the noon Sun reaches its apex on the summer solstice (avg. June 22) at a zenith angle (i.e., from overhead) of 16 degrees 28 minutes and 48 seconds when the people directly south of me on the Tropic of Cancer can see the noon Sun directly overhead. At no time during the year is my noon Sun directly overhead. And on the first days of spring and fall, I see the noon Sun at 40 degrees one minute and 12 seconds from overhead, the result of my latitude when the overhead noon Sun appears at the Equator. In the winter, my noon Sun is much lower, reflecting the 63 degrees 31 minutes and 12 seconds from my latitude to the Tropic of Capricorn at 23.5 degrees south, where the noon Sun occurs on or about December 22, the first day of my Northern Hemisphere winter.

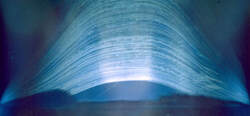

So, the Sun traces different arcs across my sky, its daily midpoint being “noon,” but never for me at about 40 degrees north latitude directly “overhead.” And it rises and sets progressively farther to the south each day from the summer solstice to the winter solstice, and then progressively farther to the north during the ensuing six months. Valkengorgh’s long exposure photo reveals that path for the University of Hertfordshire’s Bayfordbury Observatory, located north of London at latitude 51 degrees, 46 minutes, 30 seconds north, about eleven degrees farther north than my location.

As I look out the window next to my computer this December morning at 7:42, I see the Sun near its farthest southern rising position over the nearby mountain. I’ll be able to see its rise, occurring later each day and a bit more south until the winter solstice, when the point of sunrise will make its way northward, marching across my horizon progressively away from my library window and toward its summer appearance out a kitchen window on June 22. Pretty regular pattern. Heck, one could set a clock…

The old saw “a picture is worth a thousand words” applies here—in this instance the picture is worth the 406 words in the “class review notes” you just read. Regina’s long exposure captures that changing celestial path over eight years. She hasn’t made any discovery, of course, but she has done something that in the minds of the ancient Druids, the Egyptians, through the minds of Eratosthenes and everyone leading up to Ptolemy, Copernicus and Tycho Brahe took years to measure. Imagine those Druids setting up Stonehenge or the Egyptians aligning their pyramids with their latitude’s annual solar paths without the precise observations they made over decades, centuries, or maybe even millennia. Regina did in eight years what our ancient ancestors did over the courses of their civilizations. And she did it with a pinhole in a beer can!**

Obviously, there’s something to be said for beer in this, such as its imparting in three cans or steins a belief that one can see more clearly and solve the world’s problems more astutely on the drink. There might also be something to be said for cheap simplicity. A can of beer is far less expensive than a smaller quantity of wine or an even smaller quantity of Scotch, both obtained in bottles that wouldn’t serve Regina’s purpose. We don’t have her direct account of her motives, but we can without harm assume that she might have begun the experiment in student poverty. That she was a university student suggests she was “not unfamiliar” with beer or with sources for empty beer cans. With regard to the simplicity of her apparatus, we might note that Regina placed her pinhole can camera at the site of expensive and sophisticated telescopes, so she needed neither money nor advanced and complicated technology for her revealing photo.

Most college-age students would have serious questions, of course. “What did you do with the beer, Regina?” “Who cares about the Sun’s position during different days of the year?” “Do you have any full cans left?”

Try explaining to those who make no specific observations of their world that what they believe to be so and accept as true, isn’t, in fact, reality. I have, for example, attempted to explain to college students the angle of the Sun (which ephemeral tables catalog for anyone using a sextant to navigate on the ocean) only to find that many who live north of the Tropic of Cancer believe the noon Sun occurs overhead. And I have supposed that university professors in the Southern Hemisphere south of the Tropic of Capricorn encounter the same faulty perception. Have students never looked up at noon? For many heads that have never turned skyward to check, a noon overhead sun is the supposed reality.

What could be more evident than the Sun? And yet, most people go through a lifetime without considering that what they believe about the Sun really isn’t true. Is it a big deal that most people probably don’t know that the noon overhead sun occurs only between 23.5 degrees north and 23.5 degrees south? For the particular fact of Sun angle, no. Not knowing the ephemeral tables has little effect on daily lives save those sailing in pelagic waters before the age of geostationary satellites. But having a false perception might be indicative of the way our brains, and by extension, our minds work.

We live complex lives in a complex world, so we pick and choose our foci, many of which are obtained through pinhole apertures. Literally, all of us have some limitations on what we look at or on what we understand about our world. All of us see through pinholes at times. That there’s more to see than we focus on observing is inevitable. We choose consciously at times and unconsciously at others to see the world we want to see, a world visible through a tiny pinhole, one observable through a “camera” fixed for years like Regina’s beer can. It’s largely a passive system. Like Regina, once we put the can—the perspective—in place, we forget about it for years, thus getting the same view over and over.

On occasion, we rediscover the pinhole mind cameras we set up years ago and the images those cameras have taken. To our surprise, those images reveal a world we hadn’t noticed.

“Does the world really look like this?” we ask. “How could I not have seen this? All those years I assumed a different world. I guess I merely accepted rather than observed.”

*Pappas, Stephanie. 14 Dec. 2020. Longest-exposure photo ever was just discovered. It was made through a beer can. LiveScience online at

https://www.livescience.com/longest-exposure-photo-discovered-beer-can.html?utm_source=Selligent&utm_medium=email&utm_campaign=9160&utm_content=LVS_newsletter+&utm_term=2816625&m_i=RD%2B8X5LAVr4CYkLZO3KdGV3M5rrCh9iUNaNzJ_mcOLpS6U0zBrmhqDqLEaMtgYsKMZ9ZrWKO3ShvwydrwU3LEddnIE1qXkG6A6RnbO%2BRR9

**The ancients would have marveled at the beer, its container, and, of course, Regina’s photograph. They might have designated her the “queen” of science: Regina Regina.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed