Claude, interrupting his humming of “Oh! Very Young” by Cat Stevens, asks: “Do you think our early hominin ancestors were concerned about their legacies?”

Terra, looking up, says: “Strange question, but no, I don’t think habilis made tools with grandchildren in mind.”

Claude: “My brain’s been running an earworm rendition of “Oh! Very Young” by Cat Stevens, so I began thinking about why we’re here, digging around in the dirt of Tanzania.”

Terra: “Good song. Well, isn’t why we’re here obvious? We’re looking for ancient signs of human habitation, the bits and pieces of stone ancient hominins used as tools and maybe, if we’re really lucky, their bones. Maybe we’ll find the next ‘Lucy,’ only ours will be a rather complete skeleton of Homo habilis. There’s a publication and maybe even a book deal in that, maybe some fame, possibly our own legacy among paleoanthropologists. But definitely, I’m getting a dissertation out of this and probably a position in a university.”

Claude: “When I look through this dirt to find a piece of broken stone here or there, I see nothing to indicate that Homo habilis thought about legacy, but then, when I see garbage along the side of a highway back home, I guess I believe we do the same with our stuff, only in greater quantities. And just the way I want to ascribe or project my emotions on my dog, I suppose I anthropomorphize even other kinds of anthrops, ascribing human emotions, desires, thinking, and actions to them, and that’s what made me wonder about how they perceived the future. Do you have a will?”

Terra: “How did you get from thinking about whether ancient hominins thought about what they were leaving behind on their footpaths or in their encampments to asking me about a will?”

Claude, turning over a clod: “Well, a will is a transfer of legacy. You know, it’s the stuff you can’t take with you when you ‘ride that great white bird into heaven,’ as Cat Stevens sings. It’s your gear, your clothing, your house, maybe even your company. I’ve been wondering whether or not ancient hominins like Homo habilis, the ancestral tool-user, said upon dying, ‘I leave all my flint to my beloved spouse and my wildebeest-skin suit to my eldest child.’ That’s the kind of will I was thinking about, the stuff that can be associated with a person’s accomplishments, the kinds of life-remnants that tie the past to the future.

“In our time, we seem to think that almost everything we leave behind is significant, not just the physical and financial stuff, but also the life record. You hear legacy discussed about every leader when people say, ‘The CEO left a legacy we’ll long remember,’ or, ‘The treaty between Country A and Country B is the diplomat’s legacy,’ or even, ‘Relativity is Einstein’s legacy,’ and ‘Parson Brown’s legacy is this magnificent church and all the marriages over which he presided.’ That’s what I’m thinking when I think about either will or legacy, and that’s why I ask whether ancient hominins thought about what they were leaving behind, their legacies being the stuff of their last wills and testaments—unwritten, of course, but still associated with the accomplishments of the deceased. And I guess while I’m thinking about it, wouldn’t it be great to discover evidence that one generation of habilis looked back on a previous generation and memorialized it just as we have enshrined legacies of our predecessors in memorials, buildings, and especially in the many statues we place in town squares and public halls?”

Terra, finding no terra cotta in her sieve says without looking at Claude: “Get real. These ancient hominins didn’t have such complex thoughts or complex technologies. They didn’t even have complex language to express such thoughts as far as we know. Look! We’re digging around for two-million-year-old artifacts that are nothing more than chipped rocks, not for the marble statuary of some Homo michaelangelonensis. We don’t find statues memorializing anything or anyone until Homo sapiens fashioned those Venus figurines of 35,000 years ago, long after Homo habilis passed into the dust we’re digging up. I don’t think Homo habilis spent much time thinking about legacies, about memorializing, or about a distant future.”

Claude: “What if we could get in a hypothetical time machine? Just daydream with me for a moment under this hot sun in this rather forsaken place. Take yourself back to the time of Homo habilis, some 2 to 2.5 million years ago in northern Tanzania and pretend you are now one of the so-called tool-users, the first of your kind as later hominins reckon your kind. You find some useful stones, hard cherty, flinty stuff, that you can chip into a tool. But you are about eight miles from your open-air encampment, so you carry the stones purposefully back to your family, where you chip away. The process indicates that you have some sense of a future, if only an immediate one. I’m not saying that you could anticipate the arrival of paleoanthropologists 2 to 2.5 million years later. Heck, even as aware as I am, I still can’t imagine what hominins might do should they survive the next two million years, so, you as a member of habilis probably can’t imagine a group of your descendants arriving on the site where you live but using more sophisticated tools like shovels, picks, and theodolites connected to satellites. Purposefully leaving anything for the future might imply some understanding of how indefinite the future is.

“Back then, two million years ago, if you had foreseen this future, the one that has me digging for your tools, would you have made finding artifacts easier for me, your distant descendant? With your primitive technology would you have neatly arranged some rocks to make a stone time capsule? Would you even have cared that there would be a distant future? Or were you so wrapped up in daily life that you had little time for any speculation? Could your small brain even process a future beyond tomorrow’s need for a sharpened piece of flint? You had to have had some ability to anticipate. Shaping rocks for tools indicates at least some sense of anticipation, some ability to plan, and planning is nothing if it is not first an acknowledgement of a future.

“And if I could put you back in the time machine after you lived for a while as habilis, and then transport you to our present, what would you make of tan obsession with legacies, with all our wills, memorials, and statues? Certainly, you had back then to be aware of the passage of time as you and your family aged. Surely, that small brain of yours was aware that individuals die from disease, predation, and conflict and that others take their place just as you took the place of the previous generation and your offspring would take your place. You had to have had some sense of a future, at least of a future extending into the ensuing generation. Did it cross your mind to ask, ‘Where did all these little members of my family come from? Why am I caring for them?’

“If your tool-making was not a matter of mere instinct, if you actually ‘invented’ each new tool by taking raw rock and shaping it for a task, then surely, thought played some role in your care for your offspring. You were a tool-use who accumulated tools. So, in your old age did you hand down your stone tools as an inheritance just as the people of the twenty-first century Anno Domini might pass along the flatware and dishes of their grandparents?

“From the perspective of two million years ago, would you marvel that we pass along as our legacies not just our tools but also our thoughts? Until your hominin descendants learned to paint on rocks and cave walls long after your species became extinct, no such legacies persisted. Could you tell stories? Relate histories? If I traveled to visit you way back then would I find that you are mute around the campfire as you chip your stone tools? Did you even have controlled fire? We have no evidence that you had fires even though we have evidence that you chipped flint. Surely, you noticed the sparks? Surely, you accidentally ignited some nearby dry brush. But you left us nothing about fire or stories. Two million years might have passed till your hominin descendants learned to control fire and Prometheus-like passed on that ‘tool’ to me.

“In that youas Ms. Habilis and I as Mr. Sapiens are tool-users, we have a commonality. In that you and I both leave stuff just lying around, you know, the way your species leaves chipped stones on the ground and my species leaves garbage thrown from car windows, in that way, in leaving stuff without much thought you ancient representative of habilis and I modern representative of sapiens are much alike. But we differ in that I am more aware of a deeper past and of a myriad of possible futures. And my species leaves more stuff randomly lying around. Unlike you, habilis, I might be concerned about leaving something not just for the next generation but for multiple generations, my legacy lying not just in my tools, but importantly, in massive pyramids and even more so in thought. Isn’t it that legacy of thought that distinguishes me as much as anything else from you on a level you could not understand? I am both closely related to and widely different from your species, Ms. Terra Habilis.”

Terra, resuming her digging: “I know one thing. If I got into that time machine to go back, I wouldn’t hear such a long-winded rambling. Let’s focus on the present which is supposed to be devoted to digging up the past. Do I want to have a legacy? Sure. I’d like people to remember me, and I’d like to leave the world a better place than I found it, whatever ‘better’ means. Maybe I’ll discover something in these scattered remnants that will explain why we are what we are and why we are so different from our ancient ancestors. Maybe I’ll be the one to definitively prove that habilis was concerned more about the present than the future. Or, maybe I’ll be the one to discover that habilis did think about the future. If just one of these stone artifacts looked like a statue, I would discover that just as we look to the past, work in the present, and plan for legacies, so habilis did the same.”

Claude, singing:

Oh very young, what will you leave us this time

You're only dancing on this earth for a short while

And though your dreams may toss and turn you now

They will vanish away like your daddy's best jeans

Denim blue, fading up to the sky

And though you want them to last forever, you know they never will

And the patches make the goodbye harder still…

…And though you want to last forever, you know you never will

And the goodbye makes the journey harder still

Terra, thinking aloud and raising an eyebrow: Did habilis women have to listen to singing habilis men?

Notes:

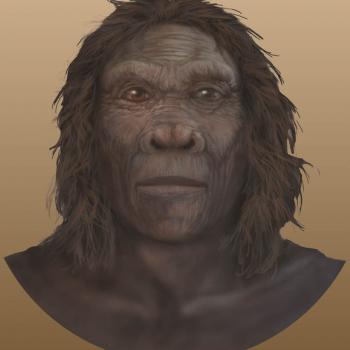

*SciNews. 2-Million-Year-Old Stone Tools Unearthed in Tanzania. 11 Jan 2021 Online at http://www.sci-news.com/archaeology/ewass-oldupa-stone-tools-09236.html Accessed January 15, 2012. Drawings of habilis are speculative, of course, but there is one in the Smithsonian makes the species human-like: https://humanorigins.si.edu/evidence/human-fossils/species/homo-habilis It is the Smithsonian image I have included here.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed