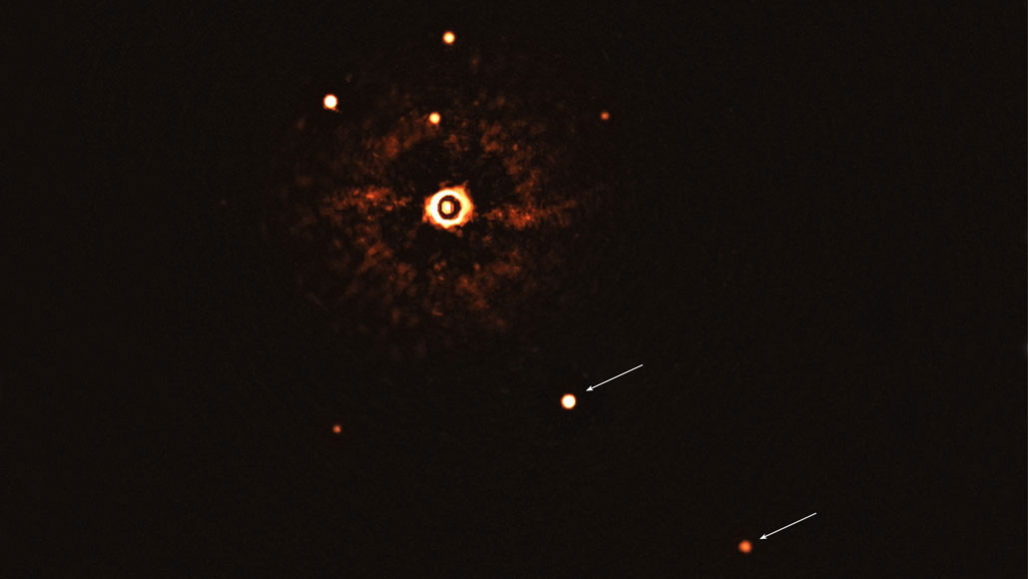

VLT image of TYC 8998-760-1 with two large exoplanets (see arrows)

VLT image of TYC 8998-760-1 with two large exoplanets (see arrows) I think of my own limited experiences as a child in the context of how I now view the world. On occasion, you probably also reflect on your changed perspectives. Each of us became a bit more jaded as our real and virtual experiences widened. Tough to overload senses that have been exposed to so many overloads, to things we’ve allowed ourselves to see, like TV series about detectives solving murder after murder after murder. Each episode dulling us just a bit more.

So, it’s with a little joy that I remember one “virtual” experience that dropped my jaw and opened my eyes. It was the opening scene of the story proper of Goldfinger, the scene filmed from a helicopter flying over the Fontainebleau Hotel off Collins Avenue in Miami. As a kid, I had never been to a grand hotel and had only seen the beaches of Lake Erie and New Jersey. I had no idea such grandeur existed. Sure, I had been to Pittsburgh, at that time a city of about 650,000, bustling sidewalks, tall—not in the NYC heights—buildings, and large department stores and to Cleveland, Detroit, and the then farm city Columbus. But a luxury hotel? I had never stepped into one. The Fontainebleau blew my mind. The hedonism of the scene briefly overwhelmed me. “Silly,” you think, “what a hick. How sheltered was this kid?” In a word: Sheltered. Not by anything other than relative poverty, I suppose. A hard-working father had little money for frivolity. And why spend hard-earned wages on luxuries? Especially if one survived the Great Depression and WWII. Thus, modest vacations in modest accommodations line my childhood memories.

Now, you might have little in common with my childhood limitations. You might have traveled more, seen more, and stayed in more luxurious accommodations than some seaside motel or home with a rental room. If so, I’m happy that you had your Fontainebleau experiences in person. I never saw the Fontainebleau in person until I moved to Miami during a sabbatical.

You will, of course, ask why I should entitle this piece with the names of great scientists. No, I’m not going to place myself among them. Rather, I want to note that like my great, great great grandparents, they would have a jaw-dropping, eye-widening expression if they could see an image captured by the Very Large Telescope (VLT) in Chile. The image above shows two planets orbiting the relatively young star TYC 8998-760-1, some 300 light-years away (The two large planets are identified by arrows, and the sun they orbit has a halo of debris. The other bright spots are stars.)*

Think now of the reactions that Copernicus, Galileo, Bruno, Brahe, and Kepler might have if they were alive to see the VLT image. Dropped jaws and opened eyes no doubt. I’d venture to say they would each fall into their seats.

But for you and me? Maybe just another blip in our otherwise jaded perspectives. “Ho-hum. Yeah, I’ve seen Hubble images. Heck, I just saw a video of Comet Neowise taken from the International Space Station—saved me the effort of trying to see it with my own eyes by waking up before sunrise or waiting for a cloudless night to see it just after sunset when the mosquitoes are out and hungry.”** Supersaturation of imagery from personal experiences and virtual experiences has dulled us (Though you might be an exception).

Recapturing and maintaining your childlike sense of wonder and amazement are challenging processes. The reason is simple: Both jaw-dropping and eye-widening reactions are spontaneous. You don’t plan them. And the moment after the jaw drops and the eyes widen, the dullness sets in, just as the olfactory senses dull with prolonged exposure to a scent.

And eventually Copernicus, Galileo, Bruno, Brahe, and Kepler would respond similarly. I suppose it’s human nature to become jaded. There is, after all, an evolutionary advantage to becoming so: Discovery is driven in part by boredom, by the attitude that “been there, done that, so what’s next?”

I want to leave you with another of my personal experiences, my observation of an old priest who taught at the private school I attended. He was a relatively renowned translator familiar with and literate in many languages (word was: 22 of them). Every time I saw him walk into a place with which he was familiar, he looked around as though he was seeing it for the first time. And I’m not just talking about some spectacular building, some Fontainebleau, some giant cathedral. It was even the plainest of rooms, an old classroom, for example. It’s that sense of wonder that I wish for you. Not just over an image no one has ever seen before, like planets orbiting a distant star, but over what you daily see—even though you have “been there, done that.” As you go through your day, look around. You think you’ve seen it all before, but I guarantee you missed something, and in discovering that or in rediscovering it, you will regain that spontaneity you lost.

*Grossman, Lisa. This is the first picture of a sun-like star with multiple exoplanets. ScienceNews. 22 Jul 2020. https://www.sciencenews.org/article/first-picture-sun-like-star-multiple-exoplanets-astronomy-planets Accessed August 3, 2020.

**https://video.search.yahoo.com/yhs/search?fr=yhs-iba-syn&hsimp=yhs-syn&hspart=iba&p=youtube+video+of+comet+neowise+from+ISS#id=2&vid=9ffbacde71cd4e1148ba465feb1ae9ab&action=click Accessed August 3, 2020.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed