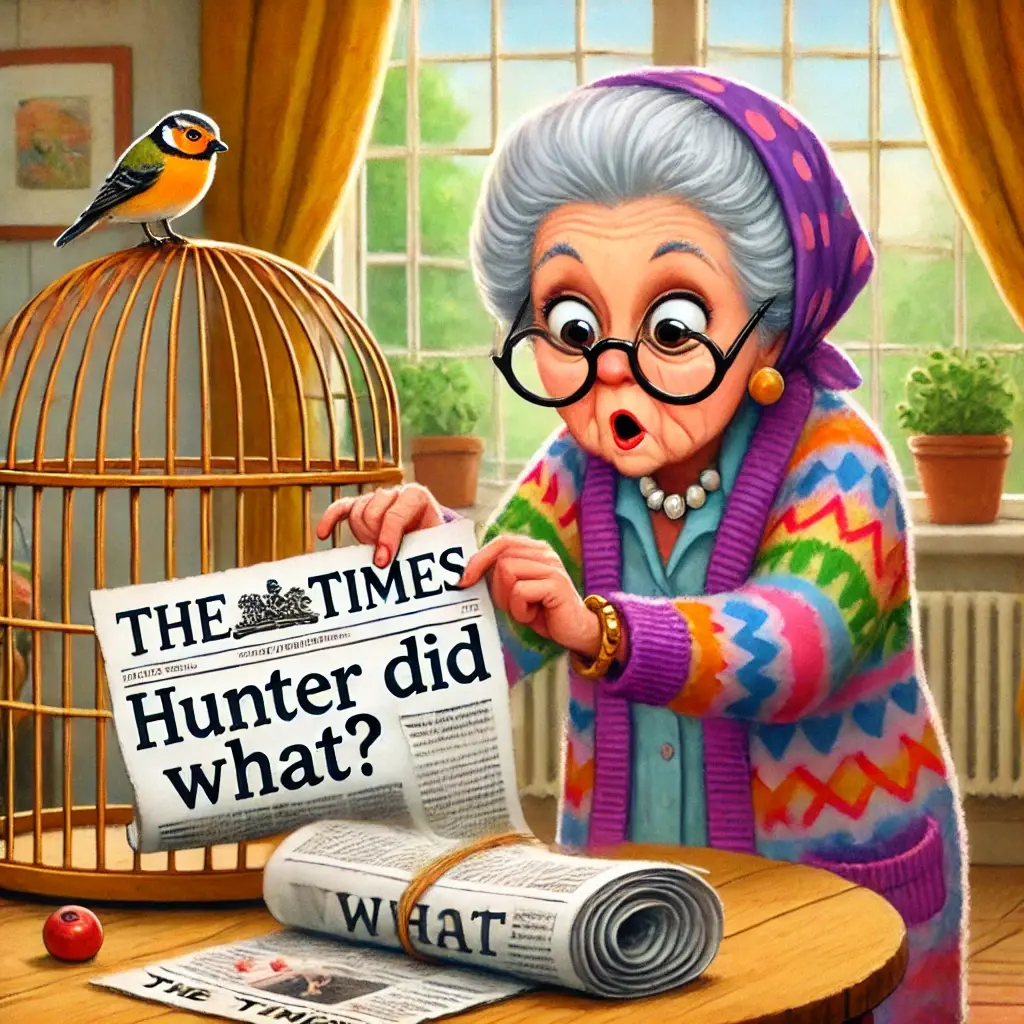

OG: I see the Press is all over the first 100 days of the Trump Administration, some favoring and some criticizing the period.

YG: Sure, he said he would end the war in Ukraine, bring down prices, et cetera.

OG: Well, ending the war in Ukraine was probably a bridge too far, given the nature of Putin, the involvement of NATO, and Zelensky’s reluctance to concede by losing Crimea and eastern Ukraine. With regard to prices, I’d say that they will come down or wages will go up to the same effect, but that the crying about prices that were coming from the Democrats was plain hypocrisy because they had no problem with 9% inflation and high prices for four years under Biden. Now inflation is back down almost to Trumpian years, those of his previous term. Nevertheless, I suspect GDP will suffer at least until new trade deals are finalized.

YG: Yeah, about those tariffs.

OG: Let me guess. You’re concerned that the stuff China sells you at Walmart will be more expensive.

YG: No doubt.

OG: Could you give me change? I want to leave Josh the waiter a tip, but I have only a hundred.

YG: Sure, Twenties and fives okay? I don’t have any ones.

OG: Yep. I’ll take five twenties and eight fives.

YG: A hundred equals five twenties. What’s with the extra $40 in fives? Hundred forty doesn’t equal a hundred.

OG: Yet, you have no problem with the trade imbalance.

YG: I don’t understand.

OG: So, you object to giving me $140 for my hundred, but you don’t object to giving China more money than China gives the US. You see the unevenness when it’s your money, your very personal up-close money, but you can’t understand that you have been giving away the country’s, and therefore your, money to China in the trade imbalance.

YG: I hadn’t thought of it that way.

OG: I understand the dissociation of personal finances and national finances, but you should understand why a little bit of economic pain in the short term can undo decades of economic pain you accepted without thinking. America can always generate more wealth, but it’s folly to continue massive trade imbalances with countries that see the US as little more than a big fat cash cow.

Now, about that change for the hundred…

En la cafetería, un señor mayor (SM) y un joven (J) conversan.

SM: Veo que la prensa está encima de los primeros 100 días del gobierno de Trump, algunos lo apoyan y otros lo critican.

J: Claro, él prometió terminar la guerra en Ucrania, bajar los precios, y todo eso.

SM: Bueno, acabar con la guerra en Ucrania era pedirle peras al olmo, considerando cómo es Putin, el involucramiento de la OTAN, y que Zelensky no quiere ceder Crimea ni el este de Ucrania. En cuanto a los precios, yo diría que o bajan solos o suben los sueldos y da lo mismo. Pero que los demócratas se quejaran tanto de los precios fue pura hipocresía, porque no dijeron nada cuando hubo 9% de inflación y precios por las nubes durante cuatro años con Biden. Ahora la inflación casi está de vuelta a los niveles de la era Trump, de su mandato anterior. Aun así, sospecho que el PIB va a resentirse hasta que se cierren nuevos acuerdos comerciales.

J: Sí, sobre esos aranceles...

SM: A ver, déjame adivinar. Te preocupa que lo que compras en Walmart hecho en China te salga más caro.

J: Sin duda.

SM: ¿Me podés dar cambio? Quiero dejarle propina a Josh, el mesero, pero solo tengo un billete de cien.

J: Claro, ¿te sirven billetes de veinte y de cinco? No tengo de uno.

SM: Sí, está bien. Dame cinco de veinte y ocho de cinco.

J: Pero cien son cinco veintes. ¿Qué onda con los $40 extra en fives? Ciento cuarenta no es cien.

SM: Y sin embargo, no te molesta el desequilibrio comercial.

J: No te sigo.

SM: O sea, te molesta darme $140 por mi billete de cien, pero no te molesta que China reciba más dinero de EE.UU. del que nos da. Ves lo desigual cuando se trata de TU plata, de la que tenés en el bolsillo, pero no te das cuenta que llevás años regalándole al país asiático la plata de tu país, y por lo tanto, la tuya.

J: Nunca lo había pensado así.

SM: Entiendo que uno separe la economía personal de la nacional, pero hay que entender que un poco de dolor económico ahora puede corregir décadas de pérdida que aceptaste sin cuestionar. Estados Unidos puede generar más riqueza, claro, pero seguir manteniendo un déficit comercial enorme con países que nos ven como una vaca lechera gigante es un disparate.

Ahora sí… ¿me das el cambio del billete de cien?

RSS Feed

RSS Feed